The total fcuk-up that is 'developer relations'

I have, for about a year or so, been witnessing nightmare scenarios all around the mobile developer relations market. From global operators to handset manufacturers and ISVs, it’s more or less the same: A total, unmitigated fcuk-up.

It is laughable.

I find it hilarious and extremely sad — at the same time.

It’s hilarious because, goodness me, the organisations and well-natured people running and contributing to these programmes still don’t seem to have a clue.

And it’s sad, because mobile developers aren’t getting the resources they crave in terms of support, market access and revenues. And it’s sad because consumers are going out and buying devices and finding them wanting.

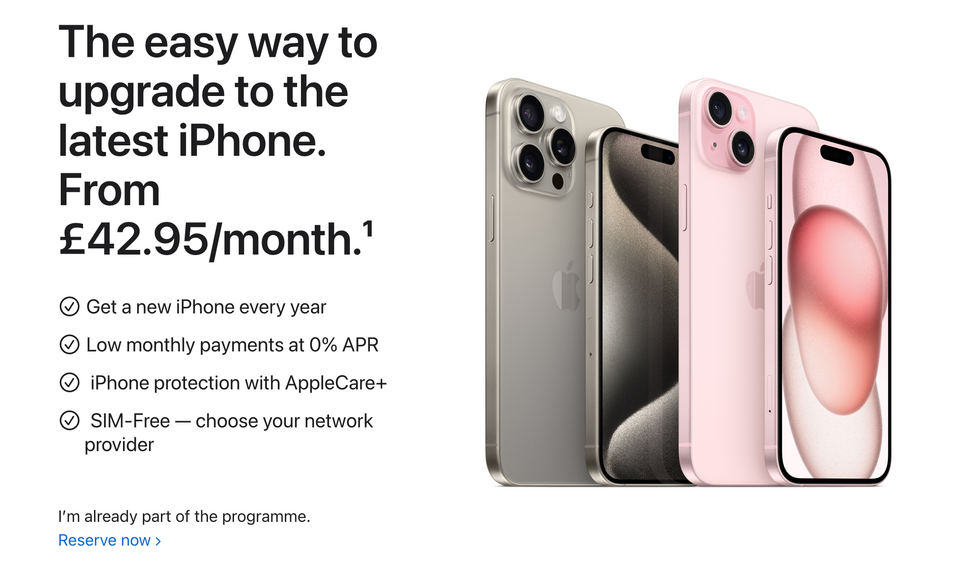

A phone is not about megapixels, or styling or how good the box is. It’s about what it *does*. It’s about the experience. And this is largely influenced by third-party developers enabling consumers to augment the standard setup defined by the manufacturer/operator/service provider.

There are three influence segments to developer relations: – brands

– programmers

– the wider market Brands are companies like Touchnote, Evernote, Shozu, Ocado, Reuters, CNN, The Telegraph, EA Mobile. They are organisations who operate mobile channels either exclusively (like Shozu, who don’t do anything else) or as a part of their business. Reuters doesn’t live or die by it’s mobile apps but it is, nonetheless, part of their strategy. Likewise with Touchnote, mobile is a key business market for them. Brands are run by non-techies, generally. There’s usually a VP or Director of Mobile who is either a bit-of-a-geek, a full-geek or entirely non-geek (and thus reliant on his/her team or the design agency/consultants). ‘Market sentiment’ is heavily influential. Programmers come in two flavours. There’s the do-ers, the ones who simply hire themselves out to make apps and then there are the entrepreneurial ones, who create apps themselves or in small teams (who then, if lucky) grow into brands. The wider market represents everyone else. Analysts, media, the whole shebang. One of the key problems with developer relations programmes is that they focus on developers. On the geeks. On the people who actually write code. This is useful, but there’s a real issue with this strategy: Developers need to get paid. They need demand from brands. Or they need very understanding wives who will let them blow the savings. They’ll certainly attend and listen carefully at developer conferences. But they’re attention is passive. That is, you’re not paying them and neither is the brand, so they’ll look and learn because it might-be-useful. But the 400-500 quid a day they’re getting for turning out so-so iPhone apps is keeping them warm at night. It’s not about the programmers. They need to be educated, they need to be given swift and efficient access to development resources, but fundamentally, the people who matter are the ones with the cash and the ability to wield it — the brands. Imagine, if you will, the Westfield shopping mall near you. Chances are it will be a fine, grand building. Thousands or car parking spaces, acres of shopping square footage — and if it’s modern, like the ones in London — the inside will resemble a palace of sorts. Bright, relaxing, welcoming. I’d like you to equate an empty brand new Westfield shopping mall with a new mobile platform. Many of the parallels are pretty striking. First off, as owner of the mall, it’s your job to get footfall, to get shoppers in the door. Or, in our example, to create appealing handsets, market them nicely and sell as many as possible. Simultaneously, or, ideally before ‘launch’, you need to be talking to the anchor tenant stores: The John Lewis, the Marks & Spencers, the massive brands. Now chances are, you’ll need to do some negotiation with the big guys. You will have to hold their hands. You will need to give them money — either in terms of reduced rent or in some cases, straight forward cash sums to help with fit out and so on. In our mobile example, you need to either help fund development for your platform, give them 100% of revenues for a year or some other incentive to guarantee they setup shop on your platform. There is nothing worse than firing up a new mobile device to check out the app store and finding it full of rubbish — and worse — unknown apps. We need to see familiar brands we recognise. I’m thinking, for example, Shazam, Google Mail, Yahoo, MSN, Reuters, BBC, Sky News. Once you’ve sorted the superstar brands, you need to work on the big brands. Like the Boots chemist, the Lush soap shop, the Timberland store, the Carphone Warehouse, GAP and so on. Again, they’re big brands so they’ll expect hand holding and some kind of financial assistance. Of course, there’s always space for the one-man-band boutique stores. They’ll get favourable terms and an opportunity to shine too — and if the customers love them, then they can be moved from those tiny aisle desk shops into bigger prominent premises. When you view mobile platforms as Westfield shopping malls, you can almost immediately see the holes in the marketing and outreach strategies. People often ask me ‘how do I do developer relations’ and I will sit them down, narrate this example and then put it into practical terms. They’re usually horrified when I indicate there’s quite a bit of footwork involved. They don’t believe me when I point out that, generally speaking, cash incentives will be required. At some point, the VP of Marketing at the handset manufacturer or operator will have gone to a conference and heard about the benefits of social media. All you need to do, they’ll have been told, is knock-up a twitter account and a Facebook page and — blow me — the developers will come running. The misconception with developers is simply shocking. How bad is it? Well, here’s one example. A global handset manufacturer to offered a pre-release handset to a well known iPhone developer — one of the superstar companies operating in the ‘new mobile sector’ (ie. iPhone only). The manufacturer was utterly shocked when the developer said ‘no, thanks’ to their offer. It’s only natural to assume that any developer would love to get a new handset to create and test their apps on, right? No. The developer in question wasn’t convinced that there was any demand and felt the manufacturer was irrelevant. Shocker. So the developer relations teams are typically ending up staring at the wall, wondering why nobody cares. It’s quite simple. It’s all about money. Nobody ever got shot for developing an iPhone app that promises to make millions and fails. Thousands would be marched straight to the firing squad if they proposed developing for anything other than iPhone, Android and possibly BlackBerry. Competitions are absolutely rubbish, generally. Look at Vodafone 360. The chap who won the hundreds of thousands of pounds prize wrote a Flickr app. A Flickr app! Not to take anything away from the chap who created it (nice one, and congratulations!) But you have to ask yourself why a) the idiots running 360 didn’t already integrate Flickr (only one of the world’s largest photo sharing communities) and why that won the prize. It’s not a new concept. It’s not, on the face of it, innovative. It’s not, I don’t believe, an app folk will be showing their friends at the pub — and it won’t, I don’t think, have hordes running to the 360 stand in the Vodafone shop. Competitions don’t work for the developer business. Why hasn’t Touchnote created a 360 app for Vodafone 360 (despite both sharing the same PR company)? Simple. They won’t make money from it. At least, they don’t think they will. Ergo they won’t. And since they’re not present on the platform, they definitely won’t! If Vodafone had offered 20k cash subsidy? I wonder if Touchnote would have taken a second look. “Why should Vodafone stump up cash?” I hear outraged 360 executives screaming, “When Apple doesn’t give anyone a penny?” Because that’s how the market is configured right now. It’s like trying to buy a new Range Rover for 5 pounds when the market wants 75k for it. You can scream all you like, you can try holding competitions, parties or tweeting like crazy, the market still wants 75k for it. So distort the market. What you want, as a manufacturer or operator, is ambivalence. You want the previously hostile developer chap to think, “You know what, since they’re offering to fund/support/sponsor the app on their platform… Yeah, screw it. Let’s do it.” Just like how the Westfield mall does it. Get your anchor tenants in. Get your big brands in, any which way. Find and curate the best stores and services — and if necessary, go to market with a wad of cash to make it happen. It’s important not to have numbskulls running the team and making the decisions though. It’s also important to have the right technical and business evangelists. The technical evangelists should — more or less — be able to write code on the platform. The business guys should be entirely switched on people, capable of joining the commercial dots and knowing how and when to influence and with the appropriate resources. And they should be giving handsets away like sweeties, to the right people at the right times. Polyester suits bearing a slide deck and a disinterested detachment are not popular with developers. The sad reality is that most developer relations strategies are adjuncts to the marketing plan. 2 people, a dog and a desk at the back of the 5th floor that nobody ever goes to. Or, 50 people trying to execute five different strategies. I’m constantly surprised at the budgets too. Enough to hold a party for 25 developers each having two drinks. Once a quarter. I’m exaggerating, but I’m not far off it. So if you’ve been wondering why most platforms you look at seem to have next to no decent apps — and if you’re wondering why nothing seems to be as good or have as much variety as the iTunes App Store, it’s because the platform owner didn’t think like a shopping mall. They thought like a platform owner. [Written on a BlackBerry Bold 9700 on the way to Paddington]

There are three influence segments to developer relations: – brands

– programmers

– the wider market Brands are companies like Touchnote, Evernote, Shozu, Ocado, Reuters, CNN, The Telegraph, EA Mobile. They are organisations who operate mobile channels either exclusively (like Shozu, who don’t do anything else) or as a part of their business. Reuters doesn’t live or die by it’s mobile apps but it is, nonetheless, part of their strategy. Likewise with Touchnote, mobile is a key business market for them. Brands are run by non-techies, generally. There’s usually a VP or Director of Mobile who is either a bit-of-a-geek, a full-geek or entirely non-geek (and thus reliant on his/her team or the design agency/consultants). ‘Market sentiment’ is heavily influential. Programmers come in two flavours. There’s the do-ers, the ones who simply hire themselves out to make apps and then there are the entrepreneurial ones, who create apps themselves or in small teams (who then, if lucky) grow into brands. The wider market represents everyone else. Analysts, media, the whole shebang. One of the key problems with developer relations programmes is that they focus on developers. On the geeks. On the people who actually write code. This is useful, but there’s a real issue with this strategy: Developers need to get paid. They need demand from brands. Or they need very understanding wives who will let them blow the savings. They’ll certainly attend and listen carefully at developer conferences. But they’re attention is passive. That is, you’re not paying them and neither is the brand, so they’ll look and learn because it might-be-useful. But the 400-500 quid a day they’re getting for turning out so-so iPhone apps is keeping them warm at night. It’s not about the programmers. They need to be educated, they need to be given swift and efficient access to development resources, but fundamentally, the people who matter are the ones with the cash and the ability to wield it — the brands. Imagine, if you will, the Westfield shopping mall near you. Chances are it will be a fine, grand building. Thousands or car parking spaces, acres of shopping square footage — and if it’s modern, like the ones in London — the inside will resemble a palace of sorts. Bright, relaxing, welcoming. I’d like you to equate an empty brand new Westfield shopping mall with a new mobile platform. Many of the parallels are pretty striking. First off, as owner of the mall, it’s your job to get footfall, to get shoppers in the door. Or, in our example, to create appealing handsets, market them nicely and sell as many as possible. Simultaneously, or, ideally before ‘launch’, you need to be talking to the anchor tenant stores: The John Lewis, the Marks & Spencers, the massive brands. Now chances are, you’ll need to do some negotiation with the big guys. You will have to hold their hands. You will need to give them money — either in terms of reduced rent or in some cases, straight forward cash sums to help with fit out and so on. In our mobile example, you need to either help fund development for your platform, give them 100% of revenues for a year or some other incentive to guarantee they setup shop on your platform. There is nothing worse than firing up a new mobile device to check out the app store and finding it full of rubbish — and worse — unknown apps. We need to see familiar brands we recognise. I’m thinking, for example, Shazam, Google Mail, Yahoo, MSN, Reuters, BBC, Sky News. Once you’ve sorted the superstar brands, you need to work on the big brands. Like the Boots chemist, the Lush soap shop, the Timberland store, the Carphone Warehouse, GAP and so on. Again, they’re big brands so they’ll expect hand holding and some kind of financial assistance. Of course, there’s always space for the one-man-band boutique stores. They’ll get favourable terms and an opportunity to shine too — and if the customers love them, then they can be moved from those tiny aisle desk shops into bigger prominent premises. When you view mobile platforms as Westfield shopping malls, you can almost immediately see the holes in the marketing and outreach strategies. People often ask me ‘how do I do developer relations’ and I will sit them down, narrate this example and then put it into practical terms. They’re usually horrified when I indicate there’s quite a bit of footwork involved. They don’t believe me when I point out that, generally speaking, cash incentives will be required. At some point, the VP of Marketing at the handset manufacturer or operator will have gone to a conference and heard about the benefits of social media. All you need to do, they’ll have been told, is knock-up a twitter account and a Facebook page and — blow me — the developers will come running. The misconception with developers is simply shocking. How bad is it? Well, here’s one example. A global handset manufacturer to offered a pre-release handset to a well known iPhone developer — one of the superstar companies operating in the ‘new mobile sector’ (ie. iPhone only). The manufacturer was utterly shocked when the developer said ‘no, thanks’ to their offer. It’s only natural to assume that any developer would love to get a new handset to create and test their apps on, right? No. The developer in question wasn’t convinced that there was any demand and felt the manufacturer was irrelevant. Shocker. So the developer relations teams are typically ending up staring at the wall, wondering why nobody cares. It’s quite simple. It’s all about money. Nobody ever got shot for developing an iPhone app that promises to make millions and fails. Thousands would be marched straight to the firing squad if they proposed developing for anything other than iPhone, Android and possibly BlackBerry. Competitions are absolutely rubbish, generally. Look at Vodafone 360. The chap who won the hundreds of thousands of pounds prize wrote a Flickr app. A Flickr app! Not to take anything away from the chap who created it (nice one, and congratulations!) But you have to ask yourself why a) the idiots running 360 didn’t already integrate Flickr (only one of the world’s largest photo sharing communities) and why that won the prize. It’s not a new concept. It’s not, on the face of it, innovative. It’s not, I don’t believe, an app folk will be showing their friends at the pub — and it won’t, I don’t think, have hordes running to the 360 stand in the Vodafone shop. Competitions don’t work for the developer business. Why hasn’t Touchnote created a 360 app for Vodafone 360 (despite both sharing the same PR company)? Simple. They won’t make money from it. At least, they don’t think they will. Ergo they won’t. And since they’re not present on the platform, they definitely won’t! If Vodafone had offered 20k cash subsidy? I wonder if Touchnote would have taken a second look. “Why should Vodafone stump up cash?” I hear outraged 360 executives screaming, “When Apple doesn’t give anyone a penny?” Because that’s how the market is configured right now. It’s like trying to buy a new Range Rover for 5 pounds when the market wants 75k for it. You can scream all you like, you can try holding competitions, parties or tweeting like crazy, the market still wants 75k for it. So distort the market. What you want, as a manufacturer or operator, is ambivalence. You want the previously hostile developer chap to think, “You know what, since they’re offering to fund/support/sponsor the app on their platform… Yeah, screw it. Let’s do it.” Just like how the Westfield mall does it. Get your anchor tenants in. Get your big brands in, any which way. Find and curate the best stores and services — and if necessary, go to market with a wad of cash to make it happen. It’s important not to have numbskulls running the team and making the decisions though. It’s also important to have the right technical and business evangelists. The technical evangelists should — more or less — be able to write code on the platform. The business guys should be entirely switched on people, capable of joining the commercial dots and knowing how and when to influence and with the appropriate resources. And they should be giving handsets away like sweeties, to the right people at the right times. Polyester suits bearing a slide deck and a disinterested detachment are not popular with developers. The sad reality is that most developer relations strategies are adjuncts to the marketing plan. 2 people, a dog and a desk at the back of the 5th floor that nobody ever goes to. Or, 50 people trying to execute five different strategies. I’m constantly surprised at the budgets too. Enough to hold a party for 25 developers each having two drinks. Once a quarter. I’m exaggerating, but I’m not far off it. So if you’ve been wondering why most platforms you look at seem to have next to no decent apps — and if you’re wondering why nothing seems to be as good or have as much variety as the iTunes App Store, it’s because the platform owner didn’t think like a shopping mall. They thought like a platform owner. [Written on a BlackBerry Bold 9700 on the way to Paddington]

Posted via email from MIR Live